07.20

This week (July 20-26) in crime history – Serial killer Alton Coleman and Debra Brown were captured in Illinois (July 20, 1984); James Holmes killed 12 and wounded 70 other at a Colorado movie theater (July 20, 2012); The Scopes Monkey Trial ends with a conviction (July 21, 1925); Terrorists attempted to bomb the London Transit system (July 21, 2005); The Preparedness Day Bombing (July 22, 1916); Serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer was arrested (July 22, 1991); John Dillinger was killed (July 22, 1934); Notorious California bandit Black Bart robbed a Wells Fargo Stagecoach (July 23, 1878); Serial killer Della Sorenson killed her first victim (July 23, 1918); Writer O. Henry was released from prison (July 24, 1901); California outlaw Joaquin Murrieta was killed (July 25, 1853); Serial killer Ed Gein died (July 26, 1984)

Highlighted Crime Story of the Week –

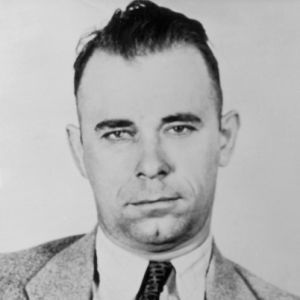

On July 22, 1934, John Dillinger, America’s “Public Enemy No. 1″ was shot and killed by FBI agents outside of the Biograph Theater in Chicago. In a fiery bank-robbing career that lasted just over a year, Dillinger and his associates robbed nearly a dozen banks, broke out of jail, and killed seven police officers and three federal agents.

John Dillinger was born in 1903 in Indianapolis, Indiana. A juvenile delinquent, he was arrested in 1924 after a botched mugging. He pleaded guilty, hoping for clemency, but was sentenced to 10 to 20 years at Pendleton Reformatory. While in prison, he made several failed escapes and was adopted by a group of professional bank robbers led by Harry Pierpont, who taught him the ways of their trade. When his friends were transferred to Indiana’s tough Michigan City Prison, he requested to be transferred there as well.

In May 1933, Dillinger was paroled, and he met up with accomplices of Pierpont. Dillinger’s plan was to raise enough funds to finance a prison break by Pierpont and the others, who then would take him on as a member of their elite robbery gang. In four months, Dillinger and his gang robbed four Indiana and Ohio banks, two grocery stores, and a drug store for a total of more than $40,000. He gained notoriety as a sharply dressed and athletic gunman who at one bank leapt over the high teller railing into the vault.

With the help of two of Pierpont’s women friends, Dillinger set up the jailbreak. Guns were bought and arranged to be smuggled into Michigan City Prison. Prison workers were bribed, and a safe house was set up. On September 22, however, just days before the jailbreak was scheduled to occur, Dillinger was arrested in Dayton, Ohio. Four days later, Pierpont and nine others broke out of Michigan City. On October 12 Pierpont came to Ohio to free Dillinger in the process the Lima sheriff was killed. On October 30, the gang robbed a police arsenal, acquiring weapons, ammunition, and bulletproof vests.

The Pierpont/Dillinger gang robbed banks in Indiana, Wisconsin, and Chicago for more than $130,000, a great fortune in the Depression era, and eluded the police in several close encounters. In January 1934, the gang headed to Tucson, Arizona, to lay low. By this time, four police officers had been killed and two wounded, and the Chicago police had established an elite squad to track down the fugitives. They were recognized in Tucson and on January 25 captured without bloodshed.

Dillinger was extradited to Indiana, arraigned for his January 15 murder of Indiana police officer William Patrick O’Malley, and held at Crown Point prison. On March 3, while still awaiting trial, he executed his most celebrated escape. That morning, he brandished a gun and methodically began locking up the prison officials. The legend is that the weapon was a wooden gun carved by Dillinger and blackened with shoe polish, but it may also have been a real gun smuggled into the prison by an associate. Whatever the case, Dillinger raided the prison arsenal, where he found two sub-machine guns, and then enlisted the aid of another prisoner, an African American man named Herbert Youngblood. Dillinger and Youngblood then made their way to the prison garage, where they stole a sheriff’s car and calmly drove away.

Parting ways with Youngblood, Dillinger traveled to Chicago and formed a new gang featuring “Baby Face” Nelson, a psychopathic killer who used to work for Al Capone. The new Dillinger gang robbed banks in South Dakota and Iowa and wounded two more police officers. The Federal Bureau of Investigation joined the manhunt for Dillinger after he escaped from Crown Point, and on March 31 two FBI agents closed in on him at an apartment in St. Paul, Minnesota. Dillinger and an accomplice shot their way out.

In April, the Dillinger gang went to hide out at a resort in Wisconsin, but the FBI was tipped off. On April 22, the FBI stormed the resort. In a disastrous operation, three civilians were mistakenly shot by the FBI, one of whom died; Baby Face Nelson killed one agent, shot another, and critically wounded a police officer; the entire Dillinger gang escaped.

With two other gang members, Dillinger traveled to Chicago, surviving a shoot-out with Minnesota police along the way. In Chicago, he lived in a safe house and got a facelift to conceal his identity. At some point, he also used acid to burn off his fingerprints. On June 30, he participated in his last robbery, in South Bend, Indiana in which one officer was killed, four civilians shot, and one gang member shot.

In July, Anna Sage, a Romanian-born brothel madam in Chicago and friend of Dillinger’s, agreed to cooperate with the FBI in exchange for leniency in an upcoming deportation hearing. She also hoped to cash in on the $10,000 bounty that had been put on his head. On July 22, Sage and Dillinger went to see the gangster movie Manhattan Melodrama at the Biograph Theater. Twenty FBI agents and police officers staked out the theater and waited for him to emerge with Sage, who would be wearing an orange dress (not red as has been erroneously reported) to identify herself.

At 10:40 p.m., Dillinger came out. Sage’s orange dress looked red under the Biographs lights, which would earn her the nickname “the lady in red.” Dillinger was ordered to surrender, but he took off running. He made it as far as an alley at the end of the block before he was gunned down, allegedly because he pulled a gun. Two bystanders were wounded in the gunfire and Dillinger was dead.

Check back every Monday for a new installment of “This Week in Crime History.” Because I will be on vacation next week’s installment will be postponed.

Michael Thomas Barry is a columnist for www.crimemagazine.com and is the author of six nonfiction books that includes the award winning Murder and Mayhem 52 Crimes that Shocked Early California, 1849-1949.

On July 21, 1899, Ernest Miller Hemingway, author of The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms and other classic works was born in Oak Park, Illinois. The influential American literary icon who tackled topics such as bullfighting and war in his work, also became famous for his own macho, hard-drinking persona. As a boy, Hemingway, the second of six children of Clarence Hemingway, a doctor, and Grace Hall Hemingway, a musician, learned to fish and hunt, which would remain lifelong passions. After graduating from high school in 1917, he volunteered for the Red Cross as an ambulance driver in Italy during World War I, he was severely wounded by mortar fire while helping an injured soldier and spent months recuperating. After the war, Hemingway returned home and married Hadley Richardson and the pair moved to Paris, France, and was part of a group of expatriate writers and artists that included F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound. In 1925, Hemingway published his first collection of short stories, which was followed by his well-received 1926 debut novel The Sun Also Rises, about a group of American and British expatriates in the 1920s who journey from Paris to Pamplona, Spain, to watch bullfighting. By the late 1920’s, Hemingway published A Farewell to Arms, divorced his first wife and married Pauline Pfeiffer, left Europe and moved to Key West, Florida. In 1932, his non-fiction book Death in the Afternoon, about bullfighting in Spain, was released. It was followed in 1935 by another non-fiction work, Green Hills of Africa, about a safari Hemingway made to East Africa in the early 1930s. During the late 1930s, Hemingway traveled to Spain to report on that country’s civil war, and also spent time living in Cuba. In 1937, he released To Have and Have Not, a novel about a fishing boat captain forced to run contraband between Key West and Cuba. In 1940, the acclaimed For Whom the Bell Tolls, about a young American fighting with a band of guerrillas in the Spanish civil war, was published. Hemingway went on to work as a war correspondent in Europe during World War II, and wrote the 1950 novel Across the River and into the Trees. Hemingway’s last significant work to be published during his lifetime was 1952’s The Old Man and the Sea, a novella about an aging Cuban fisherman that was an allegory referring to the writer’s own struggles to preserve his art in the face of fame and attention. Hemingway had become a cult figure whose four marriages and adventurous exploits in big-game hunting and fishing were widely covered in the press. But despite his fame, he had not produced a major literary work in the decade before The Old Man and the Sea debuted. The book was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1953, and Hemingway won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1954. After surviving two plane crashes in Africa in 1953, Hemingway became increasingly anxious and depressed. On July 2, 1961, he killed himself with a shotgun at his home in Ketchum, Idaho. (His father had committed suicide in 1928.) He was buried at the Ketchum Cemetery. Three novels were released posthumously, Islands in the Stream (1970), The Garden of Eden (1986) and True at First Light (1999), as was the memoir A Moveable Feast (1964), which was about his time in Paris in the 1920s. Check back every Friday for a new installment of “This Week in Literary History.” Michael Thomas Barry is the author of six nonfiction books that include the award winning Literary Legends of the British Isles (2012) and America’s Literary Legends (2014).

On July 21, 1899, Ernest Miller Hemingway, author of The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms and other classic works was born in Oak Park, Illinois. The influential American literary icon who tackled topics such as bullfighting and war in his work, also became famous for his own macho, hard-drinking persona. As a boy, Hemingway, the second of six children of Clarence Hemingway, a doctor, and Grace Hall Hemingway, a musician, learned to fish and hunt, which would remain lifelong passions. After graduating from high school in 1917, he volunteered for the Red Cross as an ambulance driver in Italy during World War I, he was severely wounded by mortar fire while helping an injured soldier and spent months recuperating. After the war, Hemingway returned home and married Hadley Richardson and the pair moved to Paris, France, and was part of a group of expatriate writers and artists that included F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound. In 1925, Hemingway published his first collection of short stories, which was followed by his well-received 1926 debut novel The Sun Also Rises, about a group of American and British expatriates in the 1920s who journey from Paris to Pamplona, Spain, to watch bullfighting. By the late 1920’s, Hemingway published A Farewell to Arms, divorced his first wife and married Pauline Pfeiffer, left Europe and moved to Key West, Florida. In 1932, his non-fiction book Death in the Afternoon, about bullfighting in Spain, was released. It was followed in 1935 by another non-fiction work, Green Hills of Africa, about a safari Hemingway made to East Africa in the early 1930s. During the late 1930s, Hemingway traveled to Spain to report on that country’s civil war, and also spent time living in Cuba. In 1937, he released To Have and Have Not, a novel about a fishing boat captain forced to run contraband between Key West and Cuba. In 1940, the acclaimed For Whom the Bell Tolls, about a young American fighting with a band of guerrillas in the Spanish civil war, was published. Hemingway went on to work as a war correspondent in Europe during World War II, and wrote the 1950 novel Across the River and into the Trees. Hemingway’s last significant work to be published during his lifetime was 1952’s The Old Man and the Sea, a novella about an aging Cuban fisherman that was an allegory referring to the writer’s own struggles to preserve his art in the face of fame and attention. Hemingway had become a cult figure whose four marriages and adventurous exploits in big-game hunting and fishing were widely covered in the press. But despite his fame, he had not produced a major literary work in the decade before The Old Man and the Sea debuted. The book was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1953, and Hemingway won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1954. After surviving two plane crashes in Africa in 1953, Hemingway became increasingly anxious and depressed. On July 2, 1961, he killed himself with a shotgun at his home in Ketchum, Idaho. (His father had committed suicide in 1928.) He was buried at the Ketchum Cemetery. Three novels were released posthumously, Islands in the Stream (1970), The Garden of Eden (1986) and True at First Light (1999), as was the memoir A Moveable Feast (1964), which was about his time in Paris in the 1920s. Check back every Friday for a new installment of “This Week in Literary History.” Michael Thomas Barry is the author of six nonfiction books that include the award winning Literary Legends of the British Isles (2012) and America’s Literary Legends (2014).

![samcustody[1]](https://michaelthomasbarry.com/wp-content/uploads//2015/06/samcustody1.gif)

![BugsySiegel[1]](https://michaelthomasbarry.com/wp-content/uploads//2015/06/BugsySiegel1.jpg)