07.10

On this date in 1889, old west gunslinger Frank “Buckskin” Leslie murders Tombstone prostitute Blonde Mollie Williams. Leslie was an ill-tempered and violent man, especially when he drank. He told conflicting stories about his early life. At times, he said he was from Texas, at other times from Kentucky. He sometimes claimed he had been trained in medicine and pharmacy, and he even boasted that he had studied in Europe. Supposedly, he earned the nickname “Buckskin” while working as an Army Scout in the Plains Indian Wars. None of his assertions can be confirmed in the historical record. The record does tell us that in 1880, Leslie opened the Cosmopolitan Hotel in the mining town of Tombstone, Arizona. Shortly thereafter, he committed his first known murder, shooting Mike Killeen in a dispute over the man’s wife. The killing was officially ruled to have been in self-defense, but suspicion of foul play arose when Leslie married Killeen’s widow two months later. Two years later, after Leslie badly pistol-whipped a man outside the Oriental Saloon, many Tombstone citizens began to suspect Leslie was a dangerous man. When the famous Tombstone gunslinger John Ringo was found murdered, suspicions again focused on Leslie, though law officers were unable to prove his guilt. Billy Claiborne, a friend of Ringo’s, was so certain Leslie was the murderer that he called him out. Leslie shot the inexperienced young man dead.

Even among the notorious rabble of gunslingers and killers in Tombstone, Leslie was unusually violent. The people of Tombstone finally had their chance to get rid of him in 1889. Two years earlier, Leslie had divorced his wife and taken up with a Tombstone prostitute named Blonde Mollie Williams. The relationship eventually soured, and in a drunken fit of rage, Leslie shot the defenseless woman dead. With testimony from a ranch hand that had witnessed the killing, a Tombstone jury convicted Leslie of murder and sentenced him to 25 years. Seven years later, Leslie won parole with the aid of a young divorcee named Belle Stowell. He soon married Stowell and seems to have made an effort to live a more peaceful life. He even reportedly made a small fortune in the Klondike Gold Rush. He moved to San Francisco in 1904. His fortunes thereafter quickly declined, and he disappeared from the historical record. He may have eventually committed suicide, but the true manner and date of his death remain unconfirmed.

On this date in 1925, the so-called “Monkey Trial” begins with John Thomas Scopes, a young high school science teacher, accused of teaching evolution in violation of a Tennessee state law. The law, which had been passed in March, made it a misdemeanor punishable by fine to “teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” With local businessman George Rappalyea, Scopes had conspired to get charged with this violation, and after his arrest the pair enlisted the aid of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to organize a defense. Hearing of this coordinated attack on Christian fundamentalism, William Jennings Bryan, the three-time Democratic presidential candidate and a fundamentalist hero, volunteered to assist the prosecution. Soon after, attorney Clarence Darrow agreed to join the ACLU in the defense, and the stage was set for one of the most famous trials in U.S. history. On July 10, the Monkey Trial got underway, and within a few days hordes of spectators and reporters had descended on Dayton as preachers set up revival tents along the city’s main street to keep the faithful stirred up. Inside the Rhea County Courthouse, the defense suffered early setbacks when Judge John Raulston ruled against their attempt to prove the law unconstitutional and then refused to end his practice of opening each day’s proceeding with prayer.

Outside, Dayton took on a carnival like atmosphere as an exhibit featuring two chimpanzees and a supposed “missing link” opened in town, and vendors sold Bibles, toy monkeys, hot dogs, and lemonade. The missing link was in fact Jo Viens of Burlington, Vermont, a 51-year-old man who was of short stature and possessed a receding forehead and a protruding jaw. One of the chimpanzees wore a plaid suit, brown fedora, white spats, and entertained Dayton’s citizens by playing around on the courthouse lawn. In the courtroom, Judge Raulston destroyed the defense’s strategy by ruling that expert scientific testimony on evolution was inadmissible, on the grounds that it was Scopes who was on trial, not the law he had violated. The next day, Raulston ordered the trial moved to the courthouse lawn, fearing that the weight of the crowd inside was in danger of collapsing the floor.

In front of several thousand spectators in the open air, Darrow changed his tactics and as his sole witness called Bryan in an attempt to discredit his literal interpretation of the Bible. In a searching examination, Bryan was subjected to severe ridicule and forced to make ignorant and contradictory statements to the amusement of the crowd. On July 21, in his closing speech, Darrow asked the jury to return a verdict of guilty in order that the case might be appealed. Under Tennessee law, Bryan was thereby denied the opportunity to deliver the closing speech he had been preparing for weeks. After eight minutes of deliberation, the jury returned with a guilty verdict, and Raulston ordered Scopes to pay a fine of $100, the minimum the law allowed. Although Bryan had won the case, he had been publicly humiliated and his fundamentalist beliefs had been disgraced. Five days later, on July 26, he lay down for a Sunday afternoon nap and died. In 1927, the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the Monkey Trial verdict on a technicality but left the constitutional issues unresolved until 1968, when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a similar Arkansas law on the grounds that it violated the First Amendment.

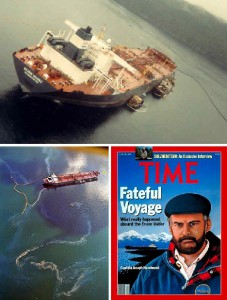

On this date in 1992, the Alaska court of appeals overturns the conviction of Joseph Hazelwood, the former captain of the oil tanker Exxon Valdez. Hazelwood, who was found guilty of negligence for his role in the massive oil spill in Prince William Sound in 1989, successfully argued that he was entitled to immunity from prosecution because he had reported the oil spill to authorities 20 minutes after the ship ran aground. The Exxon Valdez accident on the Alaskan coast was one of the largest environmental disasters in American history and resulted in the deaths of 250,000 sea birds, thousands of sea otters and seals, hundreds of bald eagles and countless salmon and herring eggs. The ship, 1,000 feet long and carrying 1.3 million barrels of oil, ran aground on Bligh Reef on March 24, 1989, after failing to return to the shipping lanes, which it had maneuvered out of to avoid icebergs. It later came to light that several officers, including Captain Hazelwood, had been drinking at a bar the night the Exxon Valdez left port. However, there wasn’t enough evidence to support the notion that alcohol impairment had been responsible for the oil spill. Rather, poor weather conditions and preparation, combined with several incompetent maneuvers by the men steering the tanker, were deemed responsible for the disaster. Captain Hazelwood, who had prior drunk driving arrests, had a spotless record as a tanker captain before the Valdez accident. Exxon compounded the environmental problems caused by the spill by not beginning the cleanup effort right away. In 1991, a civil suit resulted in a billion-dollar judgment against them. However, years later, while their appeal remained backlogged in the court system, Exxon still hadn’t paid the damages. The Exxon Valdez was repaired and had a series of different owners before being bought by a Hong Kong-based company, which renamed it the Dong Fang Ocean. It once again made headlines in November 2010 when it collided with another cargo ship off of China.