02.22

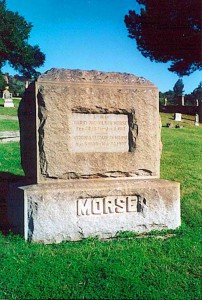

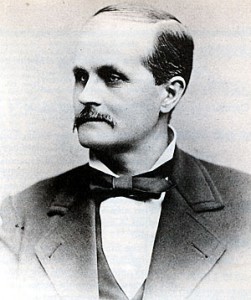

Sheriff Harry Morse (1815-1912)

It was October 1865, six months after the end of the Civil War. California was further west than what most thought of as the Wild West, but it was just as wild if not wilder than the Great Plains. The rush for gold in 1849 brought a flood of people, some good, but some bad. What attracted prospectors also attracted thieves. Vigilantes cleaned out many of the outlaw gangs but there continued to be others to replace them. Sheriff Harry Nicholson Morse was born on February 22, 1835 in New York City. He too found his way west in search of gold but soon found his true calling as Sheriff of Alameda County.

In 1865, Narrato Ponce was one of the worst of these outlaws. It was midnight on one October day when Sheriff Morse and his deputy caught up with Ponce. The outlaw was on his horse near a hideout. Morse called out for him to surrender. Ponce drew his gun and fired a fusillade of bullets. All Morse could make out in the darkness was the flashing light of the outlaw’s gun as he fired toward them. But that was enough. Morse and his deputy fired at the light. They wounded Ponce and shot his horse. But the outlaw still escaped.

Six weeks later Morse had another chance. He and two assistants cornered Ponce in Contra Costa County, California. Ponce was holed up in an adobe house with a friend. Morse and his helpers were just about to break inside when someone ran out hightailing it for the hills. The lawmen weren’t fooled into following this man, who was a decoy. A moment later Ponce leaped from the house running the opposite direction. Gunfire filled the air like it was the 4th of July in Fall. Morse followed Ponce. The moment of truth came when Morse and Ponce faced each other head to head, weapons drawn. Morse pulled the trigger on his rifle a moment before Ponce could fire. The bullet killed the outlaw instantly.

California towns in 1865 weren’t like Abilene or Dodge City, Kansas in the 70’s and 80’s. This exchange between Morse and Ponce didn’t give the lawman the reputation of a Wild Bill Hickok or Wyatt Earp. But fame was not Morse’s concern. The New York City native simply took pride in doing his job as a California sheriff. Among lawmen he was becoming increasingly respected. By the 1870’s his method of hunting down the lawless made him stand out. He rode alone into the hills and studied the areas where outlaws hid out. He made friends with ranchers and sheepherders in that area and corresponded with other lawmen to learn all he could about the outlaws’ habits.

In 1871 Morse and several others with him found themselves in Sausalito Valley, California on the trail of Juan Soto, another exceptionally dangerous killer with the nickname of the “Human Wildcat.” Back on January 10th, Soto, had robbed a store in Sunol, California. In the process, he and two partners shot and killed a clerk. In the months that followed Morse used all he had learned about the area to track down this “Human Wildcat.” Now Morse had caught up with him. They were in the mountains in the Sausalito Valley. He and a deputy named Winchell entered an adobe building where they pretty well knew they would find Soto. They were right. But Soto was not alone. Inside were a dozen of his friends. Morse drew his gun and told Deputy Winchell to handcuff Soto. Suddenly several in the room drew their guns. Winchell ran for cover. Two of Soto’s friends tried to hold Morse’s hands as Soto drew his gun to finish off the lawman. Morse broke free and fired at Soto, sending a bullet through the outlaw’s hat. Soto ran outside with Morse close behind. Soto turned and fired four bullets at Morse. The bullets missed. Then Soto rushed toward Morse. Morse rushed towards his horse for his Henry rifle. On the way he turned and fired his pistol at Soto. The bullet jammed Soto’s gun. Soto ran inside the house, picked up three pistols and ran back outside for his horse and escape. The horse shied. Soto ran for the hills. Morse made it to the Henry rifle and followed Soto in his sights. Soto was about 150 feet away when Morse leveled the rifle and fired. The bullet pierced Soto’s shoulder. Infuriated at Morse’s persistence and efficiency, Soto madly ran toward him screaming at the top of his lungs. Morse took careful aim and shot the on rushing Soto, killing him instantly.

Several months later, in October 1871, Wild Bill Hickok shot and killed Phil Coe in Abilene, Kansas. That event continues to live in Wild West history. The Morse-Soto fight received little notice. A year later (summer 1872) Harry Morse again risked his life. This time his nemesis was Tiburcio Vasquez. Again, this was one of the most dangerous and wanted men of that time.

Morse was visiting the sheriff of San Benito County in Monterey when they were interrupted with news. Vasquez along with several other outlaws had just escaped from a double holdup. The two lawmen along with a constable scrambled to their horses and rushed toward the Arroyo Cantua. The lawmen knew the outlaws would be headed toward their hideout there. Soon the two groups confronted each other. Guns blasted away and Vasquez was wounded. Though Vasquez was shot through the chest he escaped and recovered from his wound. Some-time later, Morse’s help tracked Vasquez down. The outlaw was eventually executed. Morse retired as sheriff in 1876. But his work did not end. He started a detective agency in San Francisco. He continued to do outstanding work hunting down outlaws. His most well-known case was stage robber Black Bart (Charles E. Boles). In 1883 Morse’s detective work led to Black Bart’s arrest. Through all his adventures Harry Morse escaped serious injury. Though he was often only a moment away from death when tracking the most dangerous outlaws, he never received as much attention as contemporaries Bat Masterson, Wyatt Earp, or Wild Bill Hickok. Yet he was perhaps more effective than any of them. Harry Morse died on January 11, 1912 and is buried at Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California.

![Tiburcio_Vasquez[1]](https://michaelthomasbarry.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Tiburcio_Vasquez1.png)